Most everyone knows me as someone who loves country music. But back in the glory days of 90’s country music, I hated it. I was a young tween in rural Pennsylvania with big dreams and did not want to be labeled “a hick”. Everyone knew country music was for hicks. I wanted to have great taste, be an artist, be educated. My dad singing “I like my women just a little on the trashy side” (from the distastefully named band, The Confederate Railroad) was just mortifying.

But then, it was all my parents ever played and I was a storyteller and who can resist the storytelling of Reba’s “Fancy”? I was a romantic and what romantic could resist “My Best Friend” (Tim McGraw) or “Amazed” (Lonestar) or “Strawberry Wine” (Deana Carter) or “Cowboy Take Me Away” (The Chicks, then Dixie). Probably the romance did me in more than the story-telling. Country music is very romantic.

I would sit in the front seat of my parents brown Chevy 12 passenger van, leaning on the rolled-down window, the radio and wind so loud that it drowned out the chaos of my home life, and over time it wore me down from hate into love. I’ve been a fan ever since.

Beyoncé was different. I listened and sang along to Destiny’s Child—that was the music I liked when I hated country, because it was the music of someone who wore flares, not her mother’s tapered hand-me-downs; lip gloss, not Vaseline; cucumber melon body spray, not the lingering scent of horse and safeguard soap.

But I never fell in love with Beyoncé until Lemonade. Lemonade felt like an epiphany into Beyoncé as an artist. Daddy Lessons especially sent a thrill through my entire soul—it brought back the distinct memory of the day my own father said “when trouble comes to town, and men like me come around. . . shoot” I have never belted a song as much as I have belted that one.

But Lemonade was in 2016, and Daddy Lessons a sonic one-off. I had no expectation of hearing any more country music from Beyoncé, especially with how the CMT performance was received.

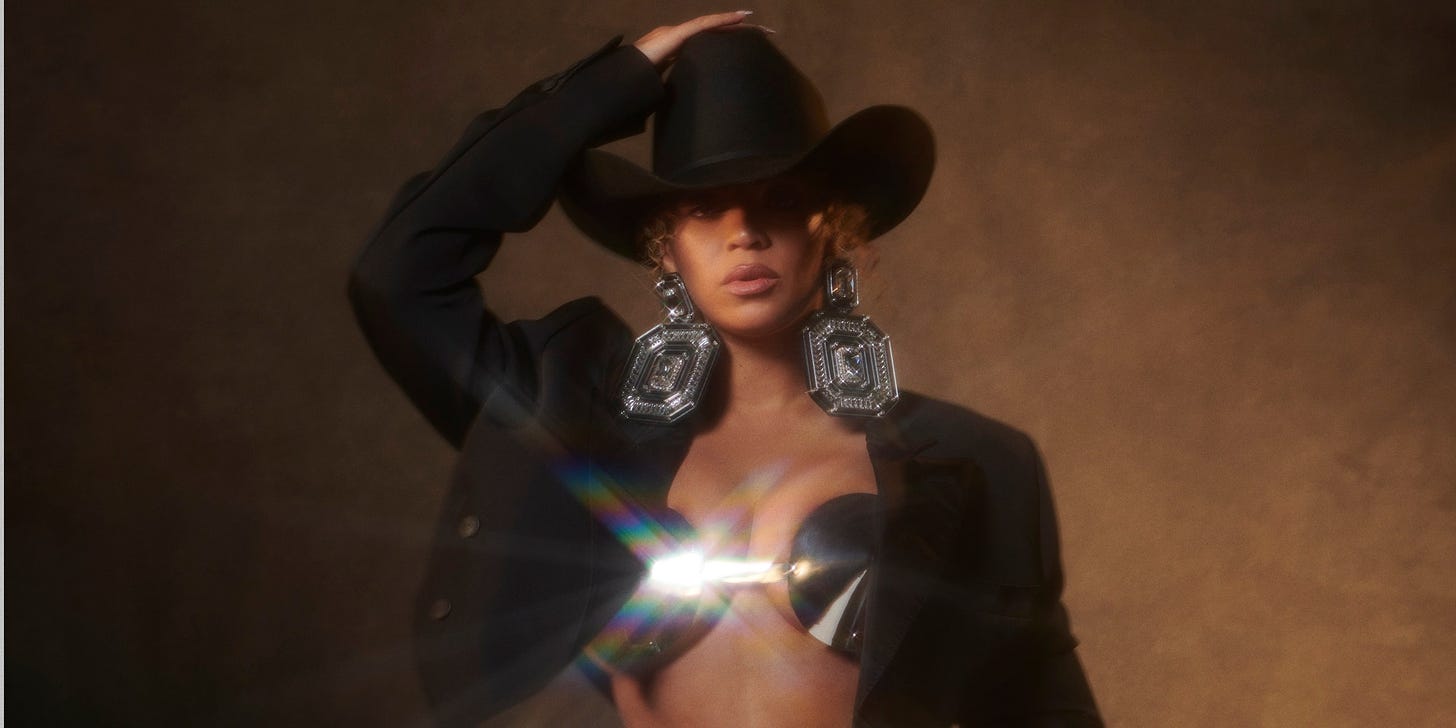

I saw her act ii announcement in a tweet—but of course it wasn’t a tweet, it was a commercial (Verizon) that led to her mic drop line “drop the new music” and her website refreshed with the announcement: new music would be dropped March 29th. Quickly, two songs followed— “Sixteen Carriages” and “Texas Hold ‘Em”.

This was a country album.

I don’t think anyone expected her to drop a country album, even people like me who stayed up to watch that CMT performance of “Daddy Lessons”. While we were all watching the romantic journey of Travis & Taylor on the field, the Queen sat back with that Mona Lisa smirk. And of course the discourse began. People laughed—country music is a joke. People were confused—isn’t country music for white people? People were worried—but country music won’t play/accept her! People were excited—people like me who have been balancing country and everything else their whole life.

As a country fan, I wanted to see especially what Beyoncé was going to do with the genre. To be frank, I wanted to defend them before I even heard them based on the strength of Daddy Lessons alone. But I was also interested in approaching the two new songs from a purely craft standpoint and whether I could objectively explain the tenants of country music and why or why not these songs adhered to the genre of country music.

A Brief History of Country Music

It’s important to know that the term “country music” and the industry that followed, wasn’t a thing until the 20’s and 30’s. The music itself originated in several different cultures—British folk music, Scotch-Irish fiddle, and the African Banjo (yes, the banjo originated in Africa). In the working class (both then and now), people mixed much more freely between races than they do in middle and upper classes and this resulted in cultural sharing. The Ballad of John Henry is a great example of a song that was born from this. In the 30’s as part of FDR’s New Deal program to promote jobs, teams from the government were sent throughout the southeastern United States to make folkway recordings. After that, it caught on as a bit of trend, called “hillbilly music” and then the 40-60’s “Country and Western”, followed by the 70’s and 80’s “Outlaw Country” era, the “Golden Era” of the 90’S and then the “Bro Country” era of the 00’s.

I’m not sure what I’d call our current era. It’s not Bro Country anymore—the radio has definitely shifted and it’s probably due to, most of all, artists like Morgan Wallen. Say what you will about Morgan’s scandals (of which there are many), he is talented and he is country. He’s also been able to bring over elements of trap, hip-hop and pop without sounding as contrived as previous artist’s attempts—something I attribute to producer Charlie Handsome (who produces for artists like Post Malone, Drake, Young Thug, Travis Scott, The Weeknd and (RIP) Juice Wrld), but also to Morgan’s actual real-life friendships and influences (the leaked video of him using the n-word was with his friends, who were black and the context did seem to be “playful” despite the broader implications of all of that1).

But more artists are following behind the influences of Wallen and also artists like Chris Stapleton, Tyler Childers, Zach Bryan and Cody Johnson and I’ve heard the last two on the radio more than once. It’s bringing back a gravely, somberness rather than the frat-boy clap tracks we’ve had for so long, and it’s refreshing.

Since the 90’s however, women have struggled to be played. This was not the case in country music until the last fifteen years. We used to be drowning in female powerhouses and they’ve created some of the most iconic country songs of all time. My theory is that the shift in trend cycle was part of the reactionary culture shift post-9/11. The “betrayal” of The Chicks truly marked the end of women in country music, at least since. And it ushered in the male swagger bro party we’ve had to limp through ever since. When someone tweeted that country music radio would never play a Black Woman I had to laugh because if you liked country music you’d know country music radio was struggling to play ANY woman.

And that is an important quirk to understand about the country music genre. Even in the streaming era, in order to succeed in country music you have to be able to get country radio on your side. There are outliers—Old Town Road and basically any woman that succeeded in the 00 Bro era were an outlier, but also artists like Kacey Musgraves and Tyler Childers had to carve out distinct followings without getting consistent radio play. But for most artists, radio is still king (and I use king, not queen, because country radio is a lot of men.) This need for country radio, not just streams is why you saw people calling their radio stations to request Beyoncé.

Another quirk that people outside of country misunderstand is how country will pull sonically from every other genre, but especially pop or hip-hop. It’s easy to think (especially in the era of bro country) that this is an inferiority complex, but it’s always been part of the genre. Country music was built on musical sharing, in the same way hip-hop and rap was built on musical sampling. There’s never been a “pure” country sound, the genre has always moved and innovated by incorporating other sounds.

What Makes a Country Music Song?

All genres are defined by certain markers. In romance novels, it’s the presence of the HEA (happily ever after), in rap, it’s the distinct lyrical flow over a beat.

In country music, it’s always been the storytelling. That’s where country music starts and ends. It is a genre that is always telling a story, often confessional and intimate, and often in the first person even if it is a fictional story. Within this requirement is a secondary lyrical requirement—a country song must evoke or invoke specific cultural elements and themes to signal its “in group” status. This language changes over time, but in order to say “I’m a country artist, this is a country song” it’s important that the lyrics speak to that specific cultural experience, and it’s usually pretty clearly defined for each era. The third subset of lyrics is country is very much a duet culture, especially for big ballads.

The second marker for a country song is the presence of strings. Fiddle, Steel Guitar, Banjo, or (my favorite) the mountain dulcimer.

The third musical marker for a country song is vocal markers such as a twang, holler, callbacks, stomp clap, and/or harmony. I would also include harmonica here because it’s a voicey riff, not a core of the arrangement like strings are.

These are the elements that make a song “country”.

Daddy Lessons

Being so deeply familiar with what makes a country song, “country”, is why Daddy Lessons was immediately recognizable to me as a country song. It’s storytelling was intimate, confessional and included specific cultural markers (motorcycles, whiskey with his tea, guns, father-daughter relationship), it included strings (guitar) and it included both Beyoncé’s Houston twang, as well as vocal stylizing’s that are immediately recognizable to country people as a “holler”. It opens with a beautifully complex harmonica and even included the stomp-clap track that has been so ubiquitous in country music of this era (though of course, it was Beyoncé so it was not a Florida-Georgia Line tinny ass clap track—this is a great video about some of these sonic tics country music has latched onto).

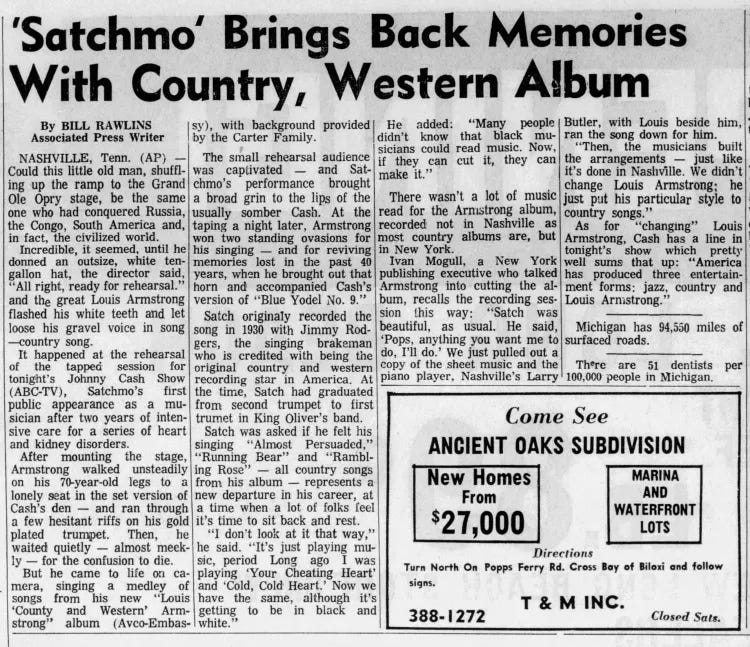

Where I think people don’t “hear” country is in the presence of the trumpet. But this already has precedent—Louis Armstrong’s 1949 song, Blue Yodel No. 9 and his 1970’s album Country & Western.

Here’s a link to Louis’s appearance on the Johnny Cash Show.

A Note About Old Town Road

A look at a Black artist moving into the country would not be complete without looking back at the controversy of Old Town Road, by Lil Nas X, in 2018. After reaching number 19 on the Billboard Country charts, the song was pulled for not fitting the country music genre (it would have hit number one if it had not been pulled). This, of course, sparked a discourse about what is country music (and do you have to be white to be “country”?).

Old Town Road, as it was originally recorded, is definitely a genre-bending country song (the lyrics are a story thematically aligned with the Outlaw Country era, the song is sonically a banjo laid in a trap beat, and Lil Nas X said himself he saw it as a “country trap” song).

But it was threatening I think, primarily, because it threatened the hegemony of country radio control over the market. It was genuinely popular without the radio--that, more than anything, was the reason for the controversy. The country music industry has a tight control over who gets to be popular and like petty deacons everywhere, they want to keep it that way. Even after it was recorded with Billy Ray Cyrus, it never reentered the country music charts.

Do People Need to Be From “The Country” to be a Country Star?

Never in the history of country music. You don’t have to be Black to be invited to the cookout, and you don’t have to be country to be a country music star. What you have to do is have the right vibe, the right story-telling feel, a feel of “authenticity”. What those words mean are fluid and ever-changing and there’s a lot of constant discussion about their meaning—this is all valid and important in any art, it means the genre is healthy and growing. But a lot of people try to use geography or aesthetics to compensate for the lack of vibe. Sometimes we let them.

Black Artists in Country Music

Like I said earlier, I think the cold reception of Beyonce at the 2016 CMT awards had as much to do with her being a Black Country singer as it did the presence of The Chicks, who have never been welcomed back into country music culture, and their overall presence as women in an industry that is so skewered male.

The country music industry is resistant of anything that doesn’t come from deep inside its machine. It’s like that even for white male artists like Tyler Childers, Sturgill Simpson, and Orville Peck—all of whom are so country they have a hard time in country music2). But of course part of the impetuous of an industry made up of white people propping themselves up as arbitrators of taste includes keeping profitable areas of industry away from Black or POC artists.

That being said, country music has always had Black artists. Charlie Pride, The Pointer Sisters, and Linda Martell, for example. In today’s market: Kane Brown, has arguably reached mainstream bro country success. Darius Rucker, the former lead singer of Hootie and the Blowfish, has had a successful transition to the country space. Most of them are men: Jimmie Allen, Blanco Brown. But there are several Black women who have had to work twice as hard and carve out their own spaces within a resistant industry, including artists such as Mickey Guyton, Rissi Palmer, Reyna Roberts and Tanner Adell.3 I will note that I don’t think any of those women have reached even remotely the same level of commercial success as their Black male counterparts.

Black Listeners of Country Music

While we’ve romanticized the idea of the white cowboy, cowboys were made up of Black, Indigenous, Meztizos, and Mexicans—so, the idea of cowboy music historically belongs in the hands of their descendants. “However, country hasn’t remained such a white genre and culture by accident, chance, or consumer preference. Nowhere in music do racist systems and practices so closely mirror that of the nation than in the country genre.” (Variety) I for one, am ready for a renassaince of Black ownership of country music.

Cowboy Carter

I know people on twitter hate this album title but it’s genius—it’s her last name (as The Carter’s) and also “The Carter Family” (aka June Carter Cash) was one of the biggest, most foundational acts in country music history. So it’s beautifully clever and legacy building name. Now that we have all the background information for “Cowboy Carter”. let’s take a closer look at the first two singles that were released.

Sixteen Carriages

Sixteen Carriages is a classic country ballad story about the ethos of work and labor many people carry for their families in the United States. In this way Beyonce’s confessional lyrics reflect the intimacy of her own experience and the scale of how many people, especially women, especially Black Women, have the same experiences.

It's been umpteen summers and I'm not in my bed

On the back of the bus and a bunk with the band

Goin' so hard, gotta choose myself

Underpaid and overwhelmed

I might cook, clean, but still won't fold

And

Sixteen dollars, workin' all day

Ain't got time to waste, I got art to make

I got love to create on this holy night

They won't dim my light, all these years I fight

What lyrical elements might point toward country culture specifically? The theme of work and labor is a huge presence in country music. I would argue that due to her wealth Beyonce is barred from the kind of “working class” picture of labor usually present in country music, but that doesn’t stop wealthy people from trying. To me this reads as an authentic portrayal of the intense labor she does put into her craft and has since a very young age—and thankfully, a side-step of the pitfall of trying to make that labor seem “working class” (many bros fall into this pitfall).

The motif of “long black road” is a classic country music element, similar to a “long black train” indicating a kind of death, usually spiritual. This reading makes sense alongside the reddit user “xcdevy”’s interpretation of the meaning of the sixteen carriages title and repetition.

So, lyrically, is this a country song? Absolutely.

Musically, Sixteen Carriages has a strong country sound---the slowed stomp (clap) track is both an ode to the stomp track, the ballad timing, and maybe even the Houston chopped and screwed sound. But it leads to that beautiful open strum of the steel guitar. She includes organ (not out of place in country music due to its presence in black and white churches all through the South). I think even a hater could close their eyes and imagine Chris Stapleton’s voice to that guitar and admit the sound is pure country roots and innovation.

Texas Hold ‘Em

The more commercial of the two songs, especially with social media, Texas Hold ‘Em is the strongest sonically country song of the three we’ve discussed here—it’s opening and main rhythm driver is banjo. This is a mainstream Nashville sound---as basic as basic can get to be honest. Again you have the stomp (clap) track, that driving strings rhythm and a back of acoustic guitar. Florida-Georgia Line couldn’t have made it more basic.

In some ways the super traditional sound becomes the foundation for the lyrical risk-taking. It’s not that this isn’t story-telling—the “head to the party” story is well-trod in country music—it’s that the specifics are recognizably Black. Well, look, I’m just a white girl from the country with Black friends (lol), so correct me when I’m wrong, but I have definitely seen a Lexus parked in a dirt lot of the country bar. The lyrical styling reminds me of older folks (some sugar on me, real life boogie, real life hoedown). And while Alan Jackson already sang about luxury cars, in his Golden Age hit Mercury Blues (aka, Ford’s Lexus, and also the song was originally recorded by a Black blues musician, K.C. Douglas in 1948), and the specifics of hoops, spurs, boots, are worn by cowgirls everywhere, this all combines (and in the voice of Beyoncé ) into very much the picture of a Black cowgirl culture.

All put together, Beyoncé is truly promising a renaissance of Country music and sonically and lyrically, she’s proven in these three songs to know not only her country music history but her own abilities to innovate as an artist. I look forward to reviewing the entire album when it releases March 29th.

XO,

Lemon

In my mind the way worse racism there was the industry making a point by elevating him rather than just taking the L. I also do not mean to minimize his use of that word, it’s unacceptable, full stop.

I love these three artists, but especially Orville Peck

I didn’t include Rhiannon Gibbons here just because she’s really folk, which is to mainstream country like academic publishing is to fiction publishing.

doing an entire history of country music and its genre-mashing and marginalization of women and BIPOC folks and anybody who is even vaguely outside the perceived norm to talk about beyonce—target audience hit because that audience is me. (something something let's parallel country music to the publishing industry someday.)